Facebook

Twitter

WhatsApp

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg is pleased to announce A Shipwrecked Sailor, an exhibition of eight new paintings on canvas, nine new drawings, and a site-specific mural by the London-born Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik. This is Tenvik’s second exhibition with the gallery.

Presented as part of Pinta Panamá Art Week, the show takes place in a temporary space in Casco Viejo, Panama City’s historic district—an atmospheric setting whose layered colonial architecture and baroque flair echo Tenvik’s enduring interest in history, ornamentation, and theatrical space. It marks the gallery’s first project in Central America and its fourth nomadic exhibition, following presentations in Paris and New York in 2024, and in Mexico City earlier this year.

The spirit of Carnival, central to Panamanian cultural life, resonates with Tenvik’s work. Carnival inverts social roles, masks identity, and unleashes exuberance as collective ritual. The artist’s characters are likewise caught between personas, adorned in elaborate costumes, staging their own emotional pageants. Her work is a psychological carnival: chaotic, joyous, and attuned to the symbolic power of performance.

Tenvik embraces the richness of Panama, with its layered history, tropical abundance, visual exuberance, and natural splendor. Her works feel at home in this context: riotous in color, alive with movement, and steeped in narrative intrigue. Figures emerge from lush, prop-strewn interiors like explorers from another time or characters from a half-remembered play. At the core of her practice lies a spirit of curiosity and invention, a fascination with how we perform ourselves across shifting environments and emotional climates.

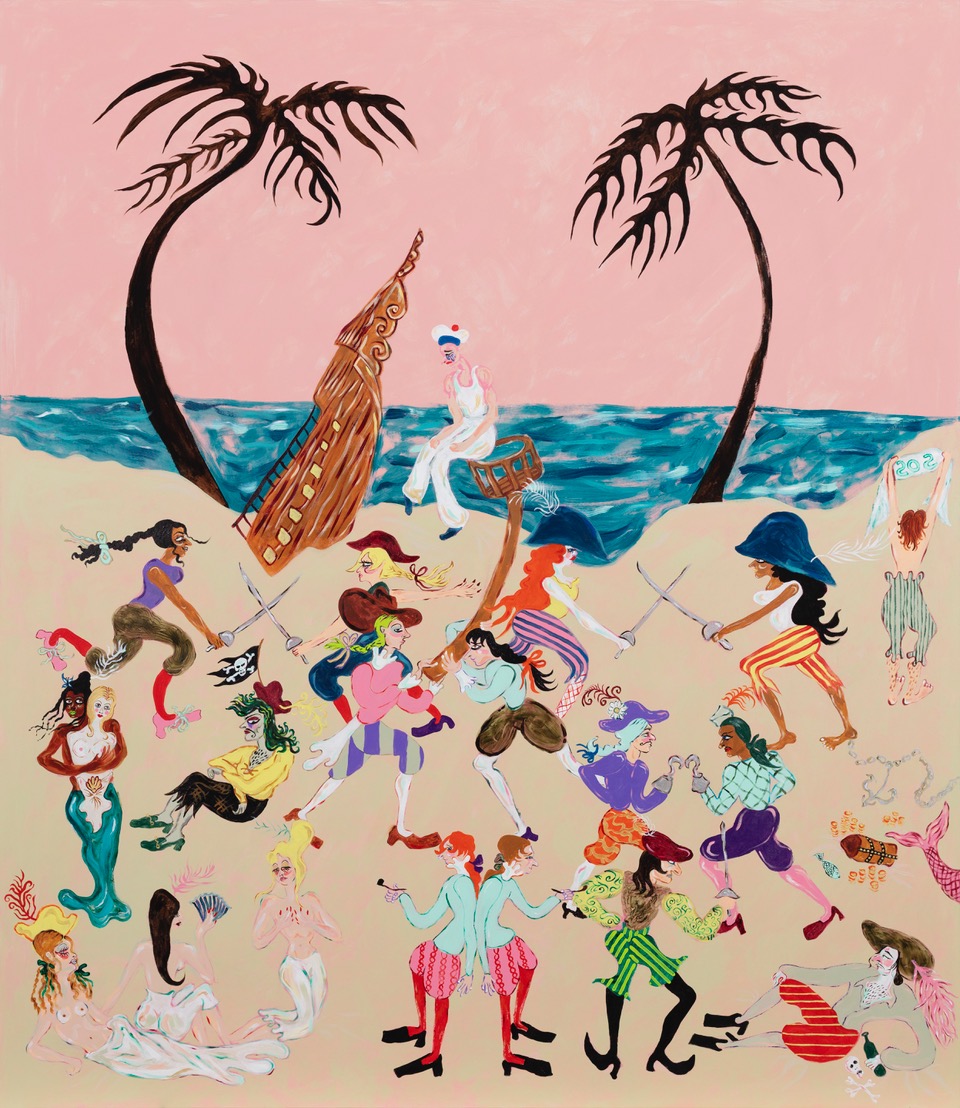

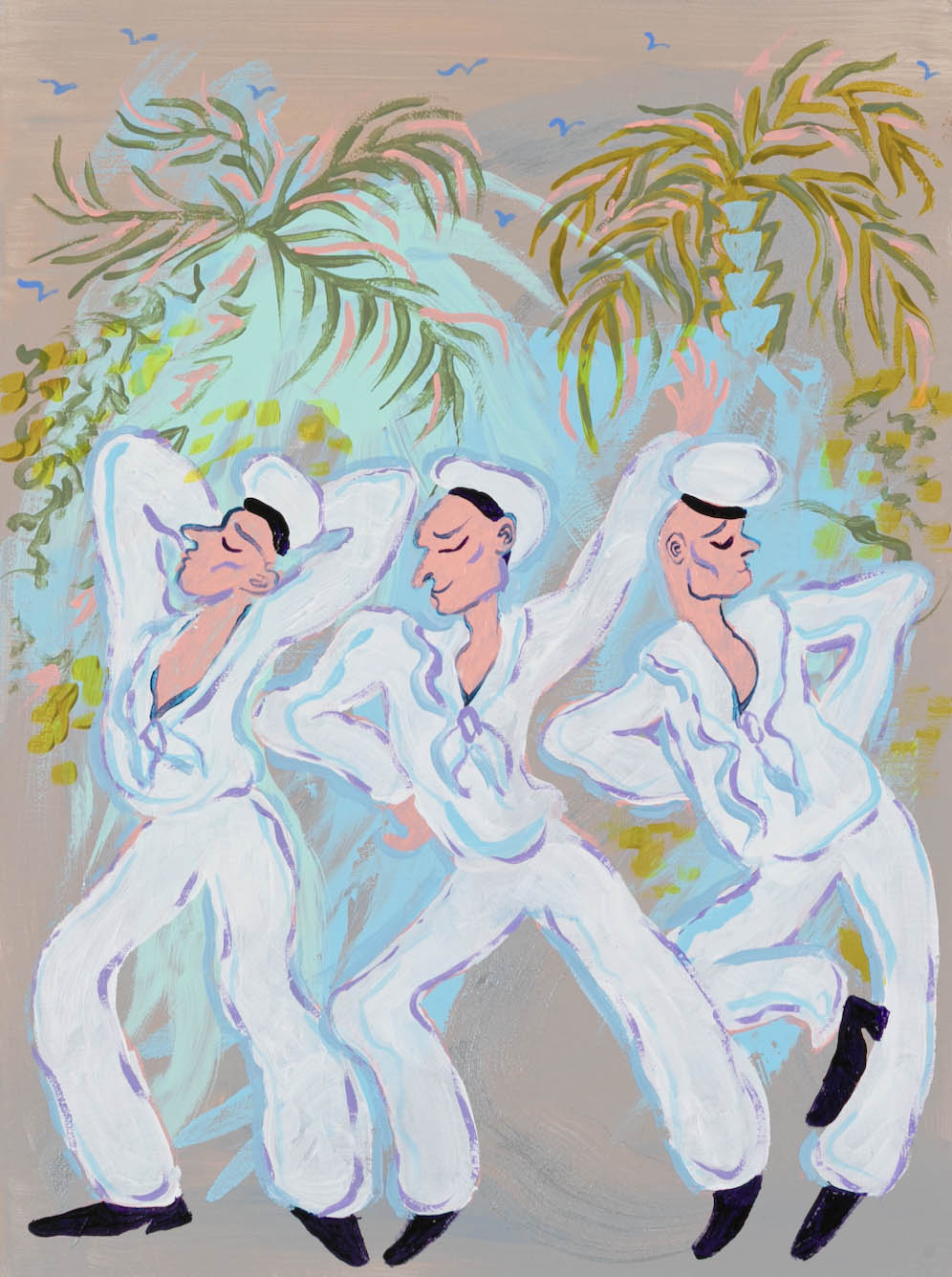

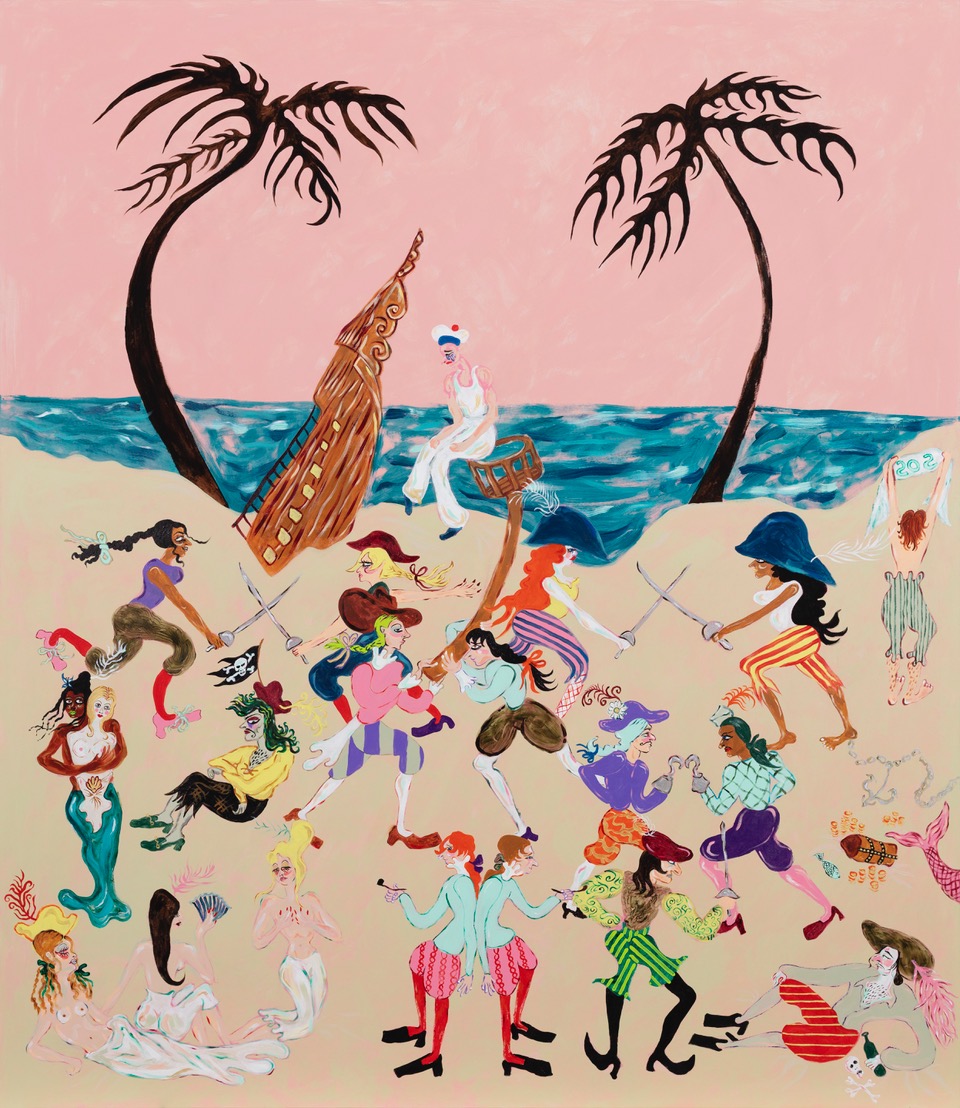

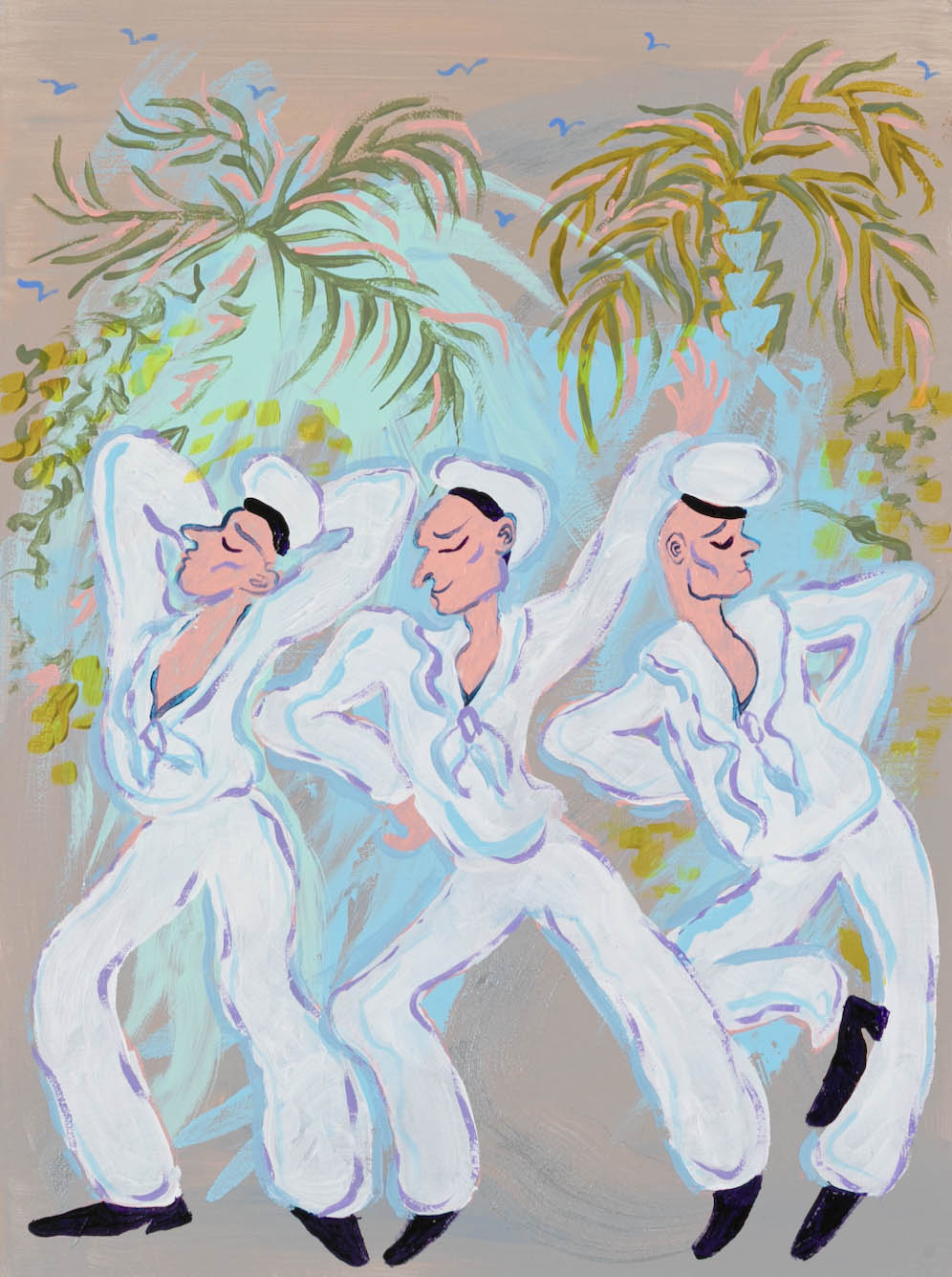

The two centerpieces of the exhibition—The Crystal Ship and The Battle of the Stranded Ones—serve as companion visions of theatrical survival and joyful collapse. In The Crystal Ship, a naval vessel is transformed into a floating stage where sailors dance, flirt, and lounge amid curling white sails. Untethered from time and expectation, the ship becomes a drifting operetta of desire, movement, and spectacle. In The Battle of the Stranded Ones, Tenvik stages a candy-colored beach scene where pirates duel, mermaids recline, and a lone sailor sits adrift on a barrel, watching the mayhem unfold. The wreckage becomes a masquerade—chaotic and campy—where identities blur and drama replaces direction. It is less a disaster than a rebirth.

A trio of smaller paintings—Floating (Mermaids), Floating (Merman), and Floating (Tritons)—form a kind of drifting triptych. In the first, mermaids glide through a pink sea, exchanging glances and secrets in a haze of intimacy. The second introduces mermen suspended in a deep blue field, serene and elusive. The third shimmers with a silvery undertow; its figures appear more statuesque, as if emerging from the depths of myth. Together, they trace a tender, melancholic, and curiously timeless emotional current.

***

Interview

In her first exhibition in Panama, Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik brings to life a maritime world populated by drifting sailors, mythological creatures, and theatrical dreamscapes. Known for her interdisciplinary approach blending painting, drawing, performance, and installation, Tenvik constructs layered environments that feel at once playful and disquieting, intelligent and intuitive. In this conversation, she speaks about myth, movement, site specificity, and why some images should behave badly.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg: Your work often moves fluidly between theatricality, historical reference, and psychological exploration. To what extent do you see your practice as a form of mythmaking, and how do you balance autobiography with invention?

Constance Tenvik: I’m drawn to themes that originate beyond myself. My work often begins with narratives I encounter in literature, theater, and history—stories that offer a kind of scaffolding. But I also gather impressions from life as it unfolds around me: gestures, movements, atmospheres. A pose I observe on the dance floor, or a figure painted on an ancient vase, might enter a drawing or a performance. I suppose I treat the world like a script in flux—open to editing, layering, and improvisation. If there’s any mythmaking in my practice, it’s less about constructing grand narratives and more about proposing alternative ways of seeing, feeling, and inhabiting time.

HMW: Across your drawings, paintings, performances, and installations, there’s a strong sense of constructed personas. What compels you toward the theme of staging, and do you see your characters as avatars, actors, or something else entirely?

CT: I’ve always been fascinated by people who carry themselves with a sense of theatrical flair—a kind of expanded expressiveness. My characters aren’t fixed identities, and they’re not stand-ins for me. They’re more like players in a shifting ensemble, caught between postures, moods, and imagined roles. Sometimes they feel like echoes from older stories; sometimes they act like performers in a scene with no director. I enjoy the ambiguity—how a figure can move from confidence to fragility, from satire to sincerity, in a single glance.

HMW: There’s a recurring motif of intricately staged interiors that, to my eye, are half-diorama, half-dreamscape. How do you conceive of space in your work? Is it psychological, theatrical, historical, or all at once?

CT: It’s a choreography of references, moods, and symbols—a kind of spatial dramaturgy. I try to create environments where different temporalities and textures can exist side by side. If we take The Crystal Ship as an example, it’s very much influenced by Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Querelle (1982), with its stylized intensity and unapologetic theatricality. When I showed an early version to my younger brother, who serves in the Navy, he joked, “Never let that ship leave land.” I understood what he meant—the sails resemble bedsheets, and the sailors seem absorbed in vignettes that have nothing to do with seamanship. The whole composition leans toward something dreamlike, or perhaps carnivalesque. What interests me are the slippages—how roles dissolve, how uniforms become patterns, how architecture becomes emotion. In that sense, space is both setting and character.

HMW: Your practice invites close looking. Each surface contains narrative cues, allusions, and visual rhythms that accumulate slowly. What role does visual density play in your work, especially at a time when minimalism often dominates cultural aesthetics?

CT: I’m interested in how much a single image or environment can contain. There’s pleasure in discovering something that wasn’t immediately visible. I think of painters like Bruegel, where you can stand back and register the scene as a whole, then lean in and find an entire world unfolding. It’s not about excess—it’s about orchestration. There’s a rhythm to how the eye moves, how attention shifts, how time slows down as you begin to notice the layers. That capacity to hold multiple energies at once is something I really value.

HMW: Your work is steeped in art history, but it never feels reverent. Instead, it’s often playful, subversive, even a bit mischievous. How do you approach the canon? Is parody a form of reverence, or is it an act of reclamation?

CT: I’ve always been curious about the so-called canon, but I don’t feel obliged to treat it with solemnity. Art history is full of intensity, contradiction, delight—so why approach it strictly with critique or distance? I’ve been absorbed by Mozart’s life and compositions, the myth of Tristan and Isolde, Rabelais’s Gargantua, fragments of Greek mythology, heraldry, jousting. When I engage with these materials, I do so with genuine excitement, but I also allow myself to respond freely—with humor, with invention, and sometimes with a touch of irreverence. It’s not parody in the strict sense. It’s more like conversation across time, opening up the possibility for other voices, other rhythms. Sometimes, misbehaving is a way of listening more closely.

HMW: This exhibition unfolds in Panama’s Casco Viejo, a place rich with colonial architecture and tropical atmosphere. How did this environment influence the tone, palette, or narrative gestures in this new body of work?

CT: This is my first time in Panama, though I recently learned it was a favorite port of my great-grandfather, who was a sailor. That added a strange and lovely layer of coincidence. I wanted to imagine a maritime world—not to document it, but to dream it into being. The works here are shaped by imagined seascapes, colored with purples, pinks, and oranges that evoke sunset skies rather than maps. It’s not about portraying the Panama Canal or its history. It’s more about channeling an atmosphere—a sense of drifting, of passage, of transformation. The sailors and mythological figures I’ve painted are suspended between the real and the imagined.

HMW: The title evokes Gabriel García Márquez’s 1955 nonfiction tale of survival and delusion. Is there a narrative thread that links the sailor’s psychological drift to the characters in your paintings and drawings?

CT: I think many people today feel as if they’re navigating uncertain waters. The idea of a shipwrecked sailor felt like a fitting starting point—adrift, unsure, searching. It’s not so much a direct link to Márquez’s story, but an emotional parallel. The figures in this exhibition carry a certain vulnerability, but also a sense of possibility. They’re suspended in a space that allows both confusion and imagination. I see the sailor not as a tragic figure, but more as someone negotiating a world without clear coordinates.

HMW: The site-specific mural suggests a kind of spatial immersion unique to this project. How do you think about scale and ephemerality when working outside the confines of the canvas or page?

CT: I love working with space as a kind of material. Last year, when I developed an installation for the Munch Museum in Oslo, I spent a lot of time working with architectural models, mapping the flow of the room, thinking about how the audience would move, where they’d pause. Scale isn’t just about dimensions—it’s about rhythm, proximity, atmosphere. And some works aren’t meant to last. That’s fine. Some things are more powerful because they’re fleeting. A mural, like a poem, doesn’t need to be permanent to matter.

HMW: Many of your figures feel caught mid-performance—oscillating between seduction, doubt, and display. In the context of Panama and its layered histories, who do you imagine your characters are performing for?

CT: Maybe they’re performing for themselves. Or for no one at all. I don’t think of them as trying to seduce or entertain. They simply inhabit their moment, with all its contradictions. They might appear extravagant, but there’s often a kind of vulnerability beneath the surface. I don’t try to pin them down. I just try to let them breathe. And now, showing this work in Panama, they’ll meet a new audience, who might read them differently—and that’s exciting. Meaning isn’t fixed. It drifts. Like a ship.

***

Constance Tenvik (b. 1990, London) was raised in Oslo and currently lives and works in New York. She received her BFA from the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo (2014) and her MFA from Yale School of Art (2016). Recent solo exhibitions have taken place at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2024); Harkawik, New York (2023); Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles (2022); Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg, Nice, France (2022); Loyal Gallery, Stockholm (2021); 56 Henry, New York (2020); and the Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo (2019), among others.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg is pleased to announce A Shipwrecked Sailor, an exhibition of eight new paintings on canvas, nine new drawings, and a site-specific mural by the London-born Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik. This is Tenvik’s second exhibition with the gallery.

Presented as part of Pinta Panamá Art Week, the show takes place in a temporary space in Casco Viejo, Panama City’s historic district—an atmospheric setting whose layered colonial architecture and baroque flair echo Tenvik’s enduring interest in history, ornamentation, and theatrical space. It marks the gallery’s first project in Central America and its fourth nomadic exhibition, following presentations in Paris and New York in 2024, and in Mexico City earlier this year.

The spirit of Carnival, central to Panamanian cultural life, resonates with Tenvik’s work. Carnival inverts social roles, masks identity, and unleashes exuberance as collective ritual. The artist’s characters are likewise caught between personas, adorned in elaborate costumes, staging their own emotional pageants. Her work is a psychological carnival: chaotic, joyous, and attuned to the symbolic power of performance.

Tenvik embraces the richness of Panama, with its layered history, tropical abundance, visual exuberance, and natural splendor. Her works feel at home in this context: riotous in color, alive with movement, and steeped in narrative intrigue. Figures emerge from lush, prop-strewn interiors like explorers from another time or characters from a half-remembered play. At the core of her practice lies a spirit of curiosity and invention, a fascination with how we perform ourselves across shifting environments and emotional climates.

The two centerpieces of the exhibition—The Crystal Ship and The Battle of the Stranded Ones—serve as companion visions of theatrical survival and joyful collapse. In The Crystal Ship, a naval vessel is transformed into a floating stage where sailors dance, flirt, and lounge amid curling white sails. Untethered from time and expectation, the ship becomes a drifting operetta of desire, movement, and spectacle. In The Battle of the Stranded Ones, Tenvik stages a candy-colored beach scene where pirates duel, mermaids recline, and a lone sailor sits adrift on a barrel, watching the mayhem unfold. The wreckage becomes a masquerade—chaotic and campy—where identities blur and drama replaces direction. It is less a disaster than a rebirth.

A trio of smaller paintings—Floating (Mermaids), Floating (Merman), and Floating (Tritons)—form a kind of drifting triptych. In the first, mermaids glide through a pink sea, exchanging glances and secrets in a haze of intimacy. The second introduces mermen suspended in a deep blue field, serene and elusive. The third shimmers with a silvery undertow; its figures appear more statuesque, as if emerging from the depths of myth. Together, they trace a tender, melancholic, and curiously timeless emotional current.

***

Interview

In her first exhibition in Panama, Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik brings to life a maritime world populated by drifting sailors, mythological creatures, and theatrical dreamscapes. Known for her interdisciplinary approach blending painting, drawing, performance, and installation, Tenvik constructs layered environments that feel at once playful and disquieting, intelligent and intuitive. In this conversation, she speaks about myth, movement, site specificity, and why some images should behave badly.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg: Your work often moves fluidly between theatricality, historical reference, and psychological exploration. To what extent do you see your practice as a form of mythmaking, and how do you balance autobiography with invention?

Constance Tenvik: I’m drawn to themes that originate beyond myself. My work often begins with narratives I encounter in literature, theater, and history—stories that offer a kind of scaffolding. But I also gather impressions from life as it unfolds around me: gestures, movements, atmospheres. A pose I observe on the dance floor, or a figure painted on an ancient vase, might enter a drawing or a performance. I suppose I treat the world like a script in flux—open to editing, layering, and improvisation. If there’s any mythmaking in my practice, it’s less about constructing grand narratives and more about proposing alternative ways of seeing, feeling, and inhabiting time.

HMW: Across your drawings, paintings, performances, and installations, there’s a strong sense of constructed personas. What compels you toward the theme of staging, and do you see your characters as avatars, actors, or something else entirely?

CT: I’ve always been fascinated by people who carry themselves with a sense of theatrical flair—a kind of expanded expressiveness. My characters aren’t fixed identities, and they’re not stand-ins for me. They’re more like players in a shifting ensemble, caught between postures, moods, and imagined roles. Sometimes they feel like echoes from older stories; sometimes they act like performers in a scene with no director. I enjoy the ambiguity—how a figure can move from confidence to fragility, from satire to sincerity, in a single glance.

HMW: There’s a recurring motif of intricately staged interiors that, to my eye, are half-diorama, half-dreamscape. How do you conceive of space in your work? Is it psychological, theatrical, historical, or all at once?

CT: It’s a choreography of references, moods, and symbols—a kind of spatial dramaturgy. I try to create environments where different temporalities and textures can exist side by side. If we take The Crystal Ship as an example, it’s very much influenced by Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Querelle (1982), with its stylized intensity and unapologetic theatricality. When I showed an early version to my younger brother, who serves in the Navy, he joked, “Never let that ship leave land.” I understood what he meant—the sails resemble bedsheets, and the sailors seem absorbed in vignettes that have nothing to do with seamanship. The whole composition leans toward something dreamlike, or perhaps carnivalesque. What interests me are the slippages—how roles dissolve, how uniforms become patterns, how architecture becomes emotion. In that sense, space is both setting and character.

HMW: Your practice invites close looking. Each surface contains narrative cues, allusions, and visual rhythms that accumulate slowly. What role does visual density play in your work, especially at a time when minimalism often dominates cultural aesthetics?

CT: I’m interested in how much a single image or environment can contain. There’s pleasure in discovering something that wasn’t immediately visible. I think of painters like Bruegel, where you can stand back and register the scene as a whole, then lean in and find an entire world unfolding. It’s not about excess—it’s about orchestration. There’s a rhythm to how the eye moves, how attention shifts, how time slows down as you begin to notice the layers. That capacity to hold multiple energies at once is something I really value.

HMW: Your work is steeped in art history, but it never feels reverent. Instead, it’s often playful, subversive, even a bit mischievous. How do you approach the canon? Is parody a form of reverence, or is it an act of reclamation?

CT: I’ve always been curious about the so-called canon, but I don’t feel obliged to treat it with solemnity. Art history is full of intensity, contradiction, delight—so why approach it strictly with critique or distance? I’ve been absorbed by Mozart’s life and compositions, the myth of Tristan and Isolde, Rabelais’s Gargantua, fragments of Greek mythology, heraldry, jousting. When I engage with these materials, I do so with genuine excitement, but I also allow myself to respond freely—with humor, with invention, and sometimes with a touch of irreverence. It’s not parody in the strict sense. It’s more like conversation across time, opening up the possibility for other voices, other rhythms. Sometimes, misbehaving is a way of listening more closely.

HMW: This exhibition unfolds in Panama’s Casco Viejo, a place rich with colonial architecture and tropical atmosphere. How did this environment influence the tone, palette, or narrative gestures in this new body of work?

CT: This is my first time in Panama, though I recently learned it was a favorite port of my great-grandfather, who was a sailor. That added a strange and lovely layer of coincidence. I wanted to imagine a maritime world—not to document it, but to dream it into being. The works here are shaped by imagined seascapes, colored with purples, pinks, and oranges that evoke sunset skies rather than maps. It’s not about portraying the Panama Canal or its history. It’s more about channeling an atmosphere—a sense of drifting, of passage, of transformation. The sailors and mythological figures I’ve painted are suspended between the real and the imagined.

HMW: The title evokes Gabriel García Márquez’s 1955 nonfiction tale of survival and delusion. Is there a narrative thread that links the sailor’s psychological drift to the characters in your paintings and drawings?

CT: I think many people today feel as if they’re navigating uncertain waters. The idea of a shipwrecked sailor felt like a fitting starting point—adrift, unsure, searching. It’s not so much a direct link to Márquez’s story, but an emotional parallel. The figures in this exhibition carry a certain vulnerability, but also a sense of possibility. They’re suspended in a space that allows both confusion and imagination. I see the sailor not as a tragic figure, but more as someone negotiating a world without clear coordinates.

HMW: The site-specific mural suggests a kind of spatial immersion unique to this project. How do you think about scale and ephemerality when working outside the confines of the canvas or page?

CT: I love working with space as a kind of material. Last year, when I developed an installation for the Munch Museum in Oslo, I spent a lot of time working with architectural models, mapping the flow of the room, thinking about how the audience would move, where they’d pause. Scale isn’t just about dimensions—it’s about rhythm, proximity, atmosphere. And some works aren’t meant to last. That’s fine. Some things are more powerful because they’re fleeting. A mural, like a poem, doesn’t need to be permanent to matter.

HMW: Many of your figures feel caught mid-performance—oscillating between seduction, doubt, and display. In the context of Panama and its layered histories, who do you imagine your characters are performing for?

CT: Maybe they’re performing for themselves. Or for no one at all. I don’t think of them as trying to seduce or entertain. They simply inhabit their moment, with all its contradictions. They might appear extravagant, but there’s often a kind of vulnerability beneath the surface. I don’t try to pin them down. I just try to let them breathe. And now, showing this work in Panama, they’ll meet a new audience, who might read them differently—and that’s exciting. Meaning isn’t fixed. It drifts. Like a ship.

***

Constance Tenvik (b. 1990, London) was raised in Oslo and currently lives and works in New York. She received her BFA from the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo (2014) and her MFA from Yale School of Art (2016). Recent solo exhibitions have taken place at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2024); Harkawik, New York (2023); Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles (2022); Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg, Nice, France (2022); Loyal Gallery, Stockholm (2021); 56 Henry, New York (2020); and the Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo (2019), among others.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg is pleased to announce A Shipwrecked Sailor, an exhibition of eight new paintings on canvas, nine new drawings, and a site-specific mural by the London-born Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik. This is Tenvik’s second exhibition with the gallery.

Presented as part of Pinta Panamá Art Week, the show takes place in a temporary space in Casco Viejo, Panama City’s historic district—an atmospheric setting whose layered colonial architecture and baroque flair echo Tenvik’s enduring interest in history, ornamentation, and theatrical space. It marks the gallery’s first project in Central America and its fourth nomadic exhibition, following presentations in Paris and New York in 2024, and in Mexico City earlier this year.

The spirit of Carnival, central to Panamanian cultural life, resonates with Tenvik’s work. Carnival inverts social roles, masks identity, and unleashes exuberance as collective ritual. The artist’s characters are likewise caught between personas, adorned in elaborate costumes, staging their own emotional pageants. Her work is a psychological carnival: chaotic, joyous, and attuned to the symbolic power of performance.

Tenvik embraces the richness of Panama, with its layered history, tropical abundance, visual exuberance, and natural splendor. Her works feel at home in this context: riotous in color, alive with movement, and steeped in narrative intrigue. Figures emerge from lush, prop-strewn interiors like explorers from another time or characters from a half-remembered play. At the core of her practice lies a spirit of curiosity and invention, a fascination with how we perform ourselves across shifting environments and emotional climates.

The two centerpieces of the exhibition—The Crystal Ship and The Battle of the Stranded Ones—serve as companion visions of theatrical survival and joyful collapse. In The Crystal Ship, a naval vessel is transformed into a floating stage where sailors dance, flirt, and lounge amid curling white sails. Untethered from time and expectation, the ship becomes a drifting operetta of desire, movement, and spectacle. In The Battle of the Stranded Ones, Tenvik stages a candy-colored beach scene where pirates duel, mermaids recline, and a lone sailor sits adrift on a barrel, watching the mayhem unfold. The wreckage becomes a masquerade—chaotic and campy—where identities blur and drama replaces direction. It is less a disaster than a rebirth.

A trio of smaller paintings—Floating (Mermaids), Floating (Merman), and Floating (Tritons)—form a kind of drifting triptych. In the first, mermaids glide through a pink sea, exchanging glances and secrets in a haze of intimacy. The second introduces mermen suspended in a deep blue field, serene and elusive. The third shimmers with a silvery undertow; its figures appear more statuesque, as if emerging from the depths of myth. Together, they trace a tender, melancholic, and curiously timeless emotional current.

***

Interview

In her first exhibition in Panama, Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik brings to life a maritime world populated by drifting sailors, mythological creatures, and theatrical dreamscapes. Known for her interdisciplinary approach blending painting, drawing, performance, and installation, Tenvik constructs layered environments that feel at once playful and disquieting, intelligent and intuitive. In this conversation, she speaks about myth, movement, site specificity, and why some images should behave badly.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg: Your work often moves fluidly between theatricality, historical reference, and psychological exploration. To what extent do you see your practice as a form of mythmaking, and how do you balance autobiography with invention?

Constance Tenvik: I’m drawn to themes that originate beyond myself. My work often begins with narratives I encounter in literature, theater, and history—stories that offer a kind of scaffolding. But I also gather impressions from life as it unfolds around me: gestures, movements, atmospheres. A pose I observe on the dance floor, or a figure painted on an ancient vase, might enter a drawing or a performance. I suppose I treat the world like a script in flux—open to editing, layering, and improvisation. If there’s any mythmaking in my practice, it’s less about constructing grand narratives and more about proposing alternative ways of seeing, feeling, and inhabiting time.

HMW: Across your drawings, paintings, performances, and installations, there’s a strong sense of constructed personas. What compels you toward the theme of staging, and do you see your characters as avatars, actors, or something else entirely?

CT: I’ve always been fascinated by people who carry themselves with a sense of theatrical flair—a kind of expanded expressiveness. My characters aren’t fixed identities, and they’re not stand-ins for me. They’re more like players in a shifting ensemble, caught between postures, moods, and imagined roles. Sometimes they feel like echoes from older stories; sometimes they act like performers in a scene with no director. I enjoy the ambiguity—how a figure can move from confidence to fragility, from satire to sincerity, in a single glance.

HMW: There’s a recurring motif of intricately staged interiors that, to my eye, are half-diorama, half-dreamscape. How do you conceive of space in your work? Is it psychological, theatrical, historical, or all at once?

CT: It’s a choreography of references, moods, and symbols—a kind of spatial dramaturgy. I try to create environments where different temporalities and textures can exist side by side. If we take The Crystal Ship as an example, it’s very much influenced by Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Querelle (1982), with its stylized intensity and unapologetic theatricality. When I showed an early version to my younger brother, who serves in the Navy, he joked, “Never let that ship leave land.” I understood what he meant—the sails resemble bedsheets, and the sailors seem absorbed in vignettes that have nothing to do with seamanship. The whole composition leans toward something dreamlike, or perhaps carnivalesque. What interests me are the slippages—how roles dissolve, how uniforms become patterns, how architecture becomes emotion. In that sense, space is both setting and character.

HMW: Your practice invites close looking. Each surface contains narrative cues, allusions, and visual rhythms that accumulate slowly. What role does visual density play in your work, especially at a time when minimalism often dominates cultural aesthetics?

CT: I’m interested in how much a single image or environment can contain. There’s pleasure in discovering something that wasn’t immediately visible. I think of painters like Bruegel, where you can stand back and register the scene as a whole, then lean in and find an entire world unfolding. It’s not about excess—it’s about orchestration. There’s a rhythm to how the eye moves, how attention shifts, how time slows down as you begin to notice the layers. That capacity to hold multiple energies at once is something I really value.

HMW: Your work is steeped in art history, but it never feels reverent. Instead, it’s often playful, subversive, even a bit mischievous. How do you approach the canon? Is parody a form of reverence, or is it an act of reclamation?

CT: I’ve always been curious about the so-called canon, but I don’t feel obliged to treat it with solemnity. Art history is full of intensity, contradiction, delight—so why approach it strictly with critique or distance? I’ve been absorbed by Mozart’s life and compositions, the myth of Tristan and Isolde, Rabelais’s Gargantua, fragments of Greek mythology, heraldry, jousting. When I engage with these materials, I do so with genuine excitement, but I also allow myself to respond freely—with humor, with invention, and sometimes with a touch of irreverence. It’s not parody in the strict sense. It’s more like conversation across time, opening up the possibility for other voices, other rhythms. Sometimes, misbehaving is a way of listening more closely.

HMW: This exhibition unfolds in Panama’s Casco Viejo, a place rich with colonial architecture and tropical atmosphere. How did this environment influence the tone, palette, or narrative gestures in this new body of work?

CT: This is my first time in Panama, though I recently learned it was a favorite port of my great-grandfather, who was a sailor. That added a strange and lovely layer of coincidence. I wanted to imagine a maritime world—not to document it, but to dream it into being. The works here are shaped by imagined seascapes, colored with purples, pinks, and oranges that evoke sunset skies rather than maps. It’s not about portraying the Panama Canal or its history. It’s more about channeling an atmosphere—a sense of drifting, of passage, of transformation. The sailors and mythological figures I’ve painted are suspended between the real and the imagined.

HMW: The title evokes Gabriel García Márquez’s 1955 nonfiction tale of survival and delusion. Is there a narrative thread that links the sailor’s psychological drift to the characters in your paintings and drawings?

CT: I think many people today feel as if they’re navigating uncertain waters. The idea of a shipwrecked sailor felt like a fitting starting point—adrift, unsure, searching. It’s not so much a direct link to Márquez’s story, but an emotional parallel. The figures in this exhibition carry a certain vulnerability, but also a sense of possibility. They’re suspended in a space that allows both confusion and imagination. I see the sailor not as a tragic figure, but more as someone negotiating a world without clear coordinates.

HMW: The site-specific mural suggests a kind of spatial immersion unique to this project. How do you think about scale and ephemerality when working outside the confines of the canvas or page?

CT: I love working with space as a kind of material. Last year, when I developed an installation for the Munch Museum in Oslo, I spent a lot of time working with architectural models, mapping the flow of the room, thinking about how the audience would move, where they’d pause. Scale isn’t just about dimensions—it’s about rhythm, proximity, atmosphere. And some works aren’t meant to last. That’s fine. Some things are more powerful because they’re fleeting. A mural, like a poem, doesn’t need to be permanent to matter.

HMW: Many of your figures feel caught mid-performance—oscillating between seduction, doubt, and display. In the context of Panama and its layered histories, who do you imagine your characters are performing for?

CT: Maybe they’re performing for themselves. Or for no one at all. I don’t think of them as trying to seduce or entertain. They simply inhabit their moment, with all its contradictions. They might appear extravagant, but there’s often a kind of vulnerability beneath the surface. I don’t try to pin them down. I just try to let them breathe. And now, showing this work in Panama, they’ll meet a new audience, who might read them differently—and that’s exciting. Meaning isn’t fixed. It drifts. Like a ship.

***

Constance Tenvik (b. 1990, London) was raised in Oslo and currently lives and works in New York. She received her BFA from the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo (2014) and her MFA from Yale School of Art (2016). Recent solo exhibitions have taken place at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2024); Harkawik, New York (2023); Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles (2022); Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg, Nice, France (2022); Loyal Gallery, Stockholm (2021); 56 Henry, New York (2020); and the Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo (2019), among others.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg is pleased to announce A Shipwrecked Sailor, an exhibition of eight new paintings on canvas, nine new drawings, and a site-specific mural by the London-born Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik. This is Tenvik’s second exhibition with the gallery.

Presented as part of Pinta Panamá Art Week, the show takes place in a temporary space in Casco Viejo, Panama City’s historic district—an atmospheric setting whose layered colonial architecture and baroque flair echo Tenvik’s enduring interest in history, ornamentation, and theatrical space. It marks the gallery’s first project in Central America and its fourth nomadic exhibition, following presentations in Paris and New York in 2024, and in Mexico City earlier this year.

The spirit of Carnival, central to Panamanian cultural life, resonates with Tenvik’s work. Carnival inverts social roles, masks identity, and unleashes exuberance as collective ritual. The artist’s characters are likewise caught between personas, adorned in elaborate costumes, staging their own emotional pageants. Her work is a psychological carnival: chaotic, joyous, and attuned to the symbolic power of performance.

Tenvik embraces the richness of Panama, with its layered history, tropical abundance, visual exuberance, and natural splendor. Her works feel at home in this context: riotous in color, alive with movement, and steeped in narrative intrigue. Figures emerge from lush, prop-strewn interiors like explorers from another time or characters from a half-remembered play. At the core of her practice lies a spirit of curiosity and invention, a fascination with how we perform ourselves across shifting environments and emotional climates.

The two centerpieces of the exhibition—The Crystal Ship and The Battle of the Stranded Ones—serve as companion visions of theatrical survival and joyful collapse. In The Crystal Ship, a naval vessel is transformed into a floating stage where sailors dance, flirt, and lounge amid curling white sails. Untethered from time and expectation, the ship becomes a drifting operetta of desire, movement, and spectacle. In The Battle of the Stranded Ones, Tenvik stages a candy-colored beach scene where pirates duel, mermaids recline, and a lone sailor sits adrift on a barrel, watching the mayhem unfold. The wreckage becomes a masquerade—chaotic and campy—where identities blur and drama replaces direction. It is less a disaster than a rebirth.

A trio of smaller paintings—Floating (Mermaids), Floating (Merman), and Floating (Tritons)—form a kind of drifting triptych. In the first, mermaids glide through a pink sea, exchanging glances and secrets in a haze of intimacy. The second introduces mermen suspended in a deep blue field, serene and elusive. The third shimmers with a silvery undertow; its figures appear more statuesque, as if emerging from the depths of myth. Together, they trace a tender, melancholic, and curiously timeless emotional current.

***

Interview

In her first exhibition in Panama, Norwegian artist Constance Tenvik brings to life a maritime world populated by drifting sailors, mythological creatures, and theatrical dreamscapes. Known for her interdisciplinary approach blending painting, drawing, performance, and installation, Tenvik constructs layered environments that feel at once playful and disquieting, intelligent and intuitive. In this conversation, she speaks about myth, movement, site specificity, and why some images should behave badly.

Hoffmann Maler Wallenberg: Your work often moves fluidly between theatricality, historical reference, and psychological exploration. To what extent do you see your practice as a form of mythmaking, and how do you balance autobiography with invention?

Constance Tenvik: I’m drawn to themes that originate beyond myself. My work often begins with narratives I encounter in literature, theater, and history—stories that offer a kind of scaffolding. But I also gather impressions from life as it unfolds around me: gestures, movements, atmospheres. A pose I observe on the dance floor, or a figure painted on an ancient vase, might enter a drawing or a performance. I suppose I treat the world like a script in flux—open to editing, layering, and improvisation. If there’s any mythmaking in my practice, it’s less about constructing grand narratives and more about proposing alternative ways of seeing, feeling, and inhabiting time.

HMW: Across your drawings, paintings, performances, and installations, there’s a strong sense of constructed personas. What compels you toward the theme of staging, and do you see your characters as avatars, actors, or something else entirely?

CT: I’ve always been fascinated by people who carry themselves with a sense of theatrical flair—a kind of expanded expressiveness. My characters aren’t fixed identities, and they’re not stand-ins for me. They’re more like players in a shifting ensemble, caught between postures, moods, and imagined roles. Sometimes they feel like echoes from older stories; sometimes they act like performers in a scene with no director. I enjoy the ambiguity—how a figure can move from confidence to fragility, from satire to sincerity, in a single glance.

HMW: There’s a recurring motif of intricately staged interiors that, to my eye, are half-diorama, half-dreamscape. How do you conceive of space in your work? Is it psychological, theatrical, historical, or all at once?

CT: It’s a choreography of references, moods, and symbols—a kind of spatial dramaturgy. I try to create environments where different temporalities and textures can exist side by side. If we take The Crystal Ship as an example, it’s very much influenced by Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Querelle (1982), with its stylized intensity and unapologetic theatricality. When I showed an early version to my younger brother, who serves in the Navy, he joked, “Never let that ship leave land.” I understood what he meant—the sails resemble bedsheets, and the sailors seem absorbed in vignettes that have nothing to do with seamanship. The whole composition leans toward something dreamlike, or perhaps carnivalesque. What interests me are the slippages—how roles dissolve, how uniforms become patterns, how architecture becomes emotion. In that sense, space is both setting and character.

HMW: Your practice invites close looking. Each surface contains narrative cues, allusions, and visual rhythms that accumulate slowly. What role does visual density play in your work, especially at a time when minimalism often dominates cultural aesthetics?

CT: I’m interested in how much a single image or environment can contain. There’s pleasure in discovering something that wasn’t immediately visible. I think of painters like Bruegel, where you can stand back and register the scene as a whole, then lean in and find an entire world unfolding. It’s not about excess—it’s about orchestration. There’s a rhythm to how the eye moves, how attention shifts, how time slows down as you begin to notice the layers. That capacity to hold multiple energies at once is something I really value.

HMW: Your work is steeped in art history, but it never feels reverent. Instead, it’s often playful, subversive, even a bit mischievous. How do you approach the canon? Is parody a form of reverence, or is it an act of reclamation?

CT: I’ve always been curious about the so-called canon, but I don’t feel obliged to treat it with solemnity. Art history is full of intensity, contradiction, delight—so why approach it strictly with critique or distance? I’ve been absorbed by Mozart’s life and compositions, the myth of Tristan and Isolde, Rabelais’s Gargantua, fragments of Greek mythology, heraldry, jousting. When I engage with these materials, I do so with genuine excitement, but I also allow myself to respond freely—with humor, with invention, and sometimes with a touch of irreverence. It’s not parody in the strict sense. It’s more like conversation across time, opening up the possibility for other voices, other rhythms. Sometimes, misbehaving is a way of listening more closely.

HMW: This exhibition unfolds in Panama’s Casco Viejo, a place rich with colonial architecture and tropical atmosphere. How did this environment influence the tone, palette, or narrative gestures in this new body of work?

CT: This is my first time in Panama, though I recently learned it was a favorite port of my great-grandfather, who was a sailor. That added a strange and lovely layer of coincidence. I wanted to imagine a maritime world—not to document it, but to dream it into being. The works here are shaped by imagined seascapes, colored with purples, pinks, and oranges that evoke sunset skies rather than maps. It’s not about portraying the Panama Canal or its history. It’s more about channeling an atmosphere—a sense of drifting, of passage, of transformation. The sailors and mythological figures I’ve painted are suspended between the real and the imagined.

HMW: The title evokes Gabriel García Márquez’s 1955 nonfiction tale of survival and delusion. Is there a narrative thread that links the sailor’s psychological drift to the characters in your paintings and drawings?

CT: I think many people today feel as if they’re navigating uncertain waters. The idea of a shipwrecked sailor felt like a fitting starting point—adrift, unsure, searching. It’s not so much a direct link to Márquez’s story, but an emotional parallel. The figures in this exhibition carry a certain vulnerability, but also a sense of possibility. They’re suspended in a space that allows both confusion and imagination. I see the sailor not as a tragic figure, but more as someone negotiating a world without clear coordinates.

HMW: The site-specific mural suggests a kind of spatial immersion unique to this project. How do you think about scale and ephemerality when working outside the confines of the canvas or page?

CT: I love working with space as a kind of material. Last year, when I developed an installation for the Munch Museum in Oslo, I spent a lot of time working with architectural models, mapping the flow of the room, thinking about how the audience would move, where they’d pause. Scale isn’t just about dimensions—it’s about rhythm, proximity, atmosphere. And some works aren’t meant to last. That’s fine. Some things are more powerful because they’re fleeting. A mural, like a poem, doesn’t need to be permanent to matter.

HMW: Many of your figures feel caught mid-performance—oscillating between seduction, doubt, and display. In the context of Panama and its layered histories, who do you imagine your characters are performing for?

CT: Maybe they’re performing for themselves. Or for no one at all. I don’t think of them as trying to seduce or entertain. They simply inhabit their moment, with all its contradictions. They might appear extravagant, but there’s often a kind of vulnerability beneath the surface. I don’t try to pin them down. I just try to let them breathe. And now, showing this work in Panama, they’ll meet a new audience, who might read them differently—and that’s exciting. Meaning isn’t fixed. It drifts. Like a ship.

***

Constance Tenvik (b. 1990, London) was raised in Oslo and currently lives and works in New York. She received her BFA from the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo (2014) and her MFA from Yale School of Art (2016). Recent solo exhibitions have taken place at the Munch Museum, Oslo (2024); Harkawik, New York (2023); Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles (2022); Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg, Nice, France (2022); Loyal Gallery, Stockholm (2021); 56 Henry, New York (2020); and the Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo (2019), among others.