Facebook

Twitter

WhatsApp

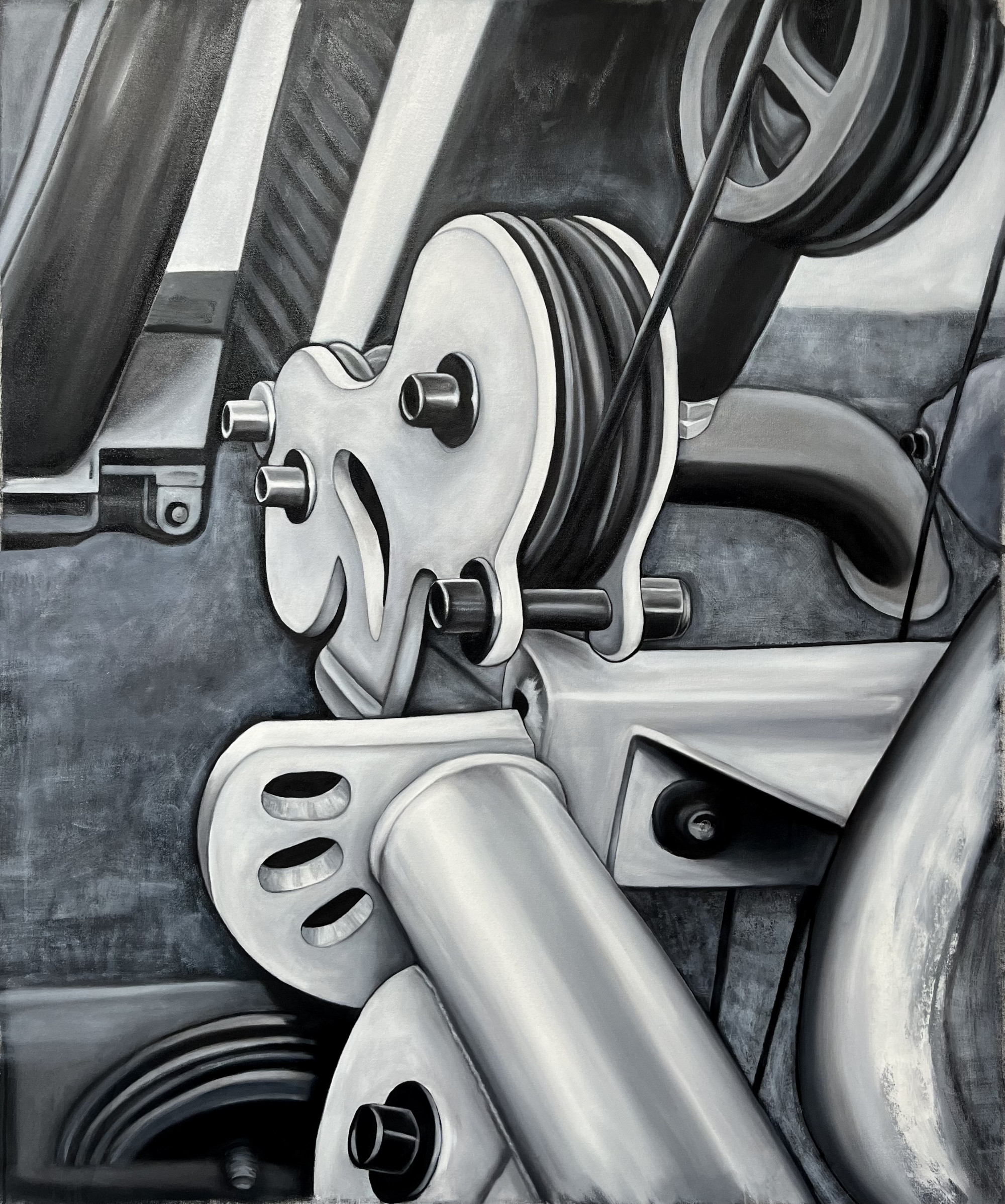

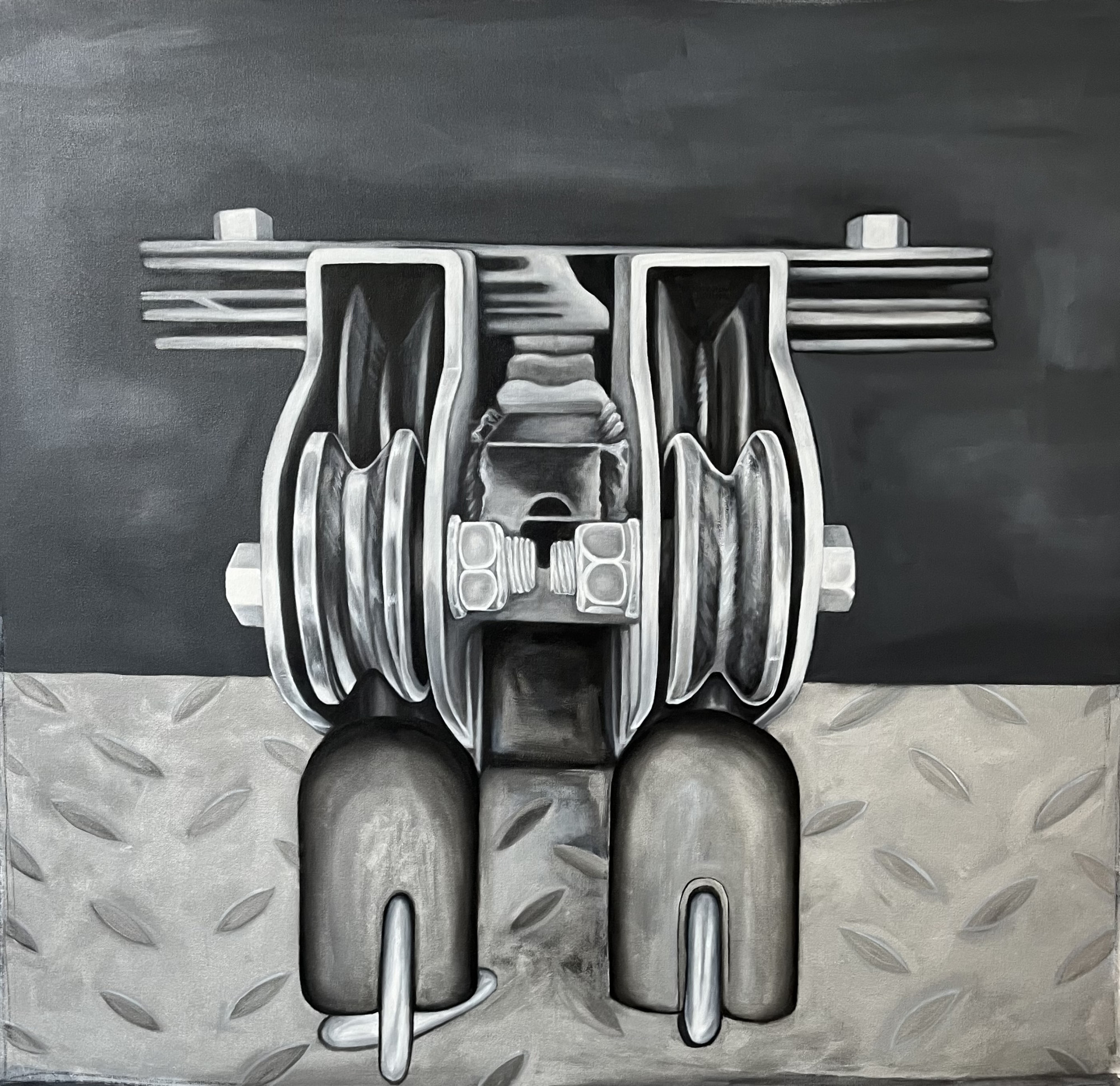

Marika Thunder

Agnes

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Anuk

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

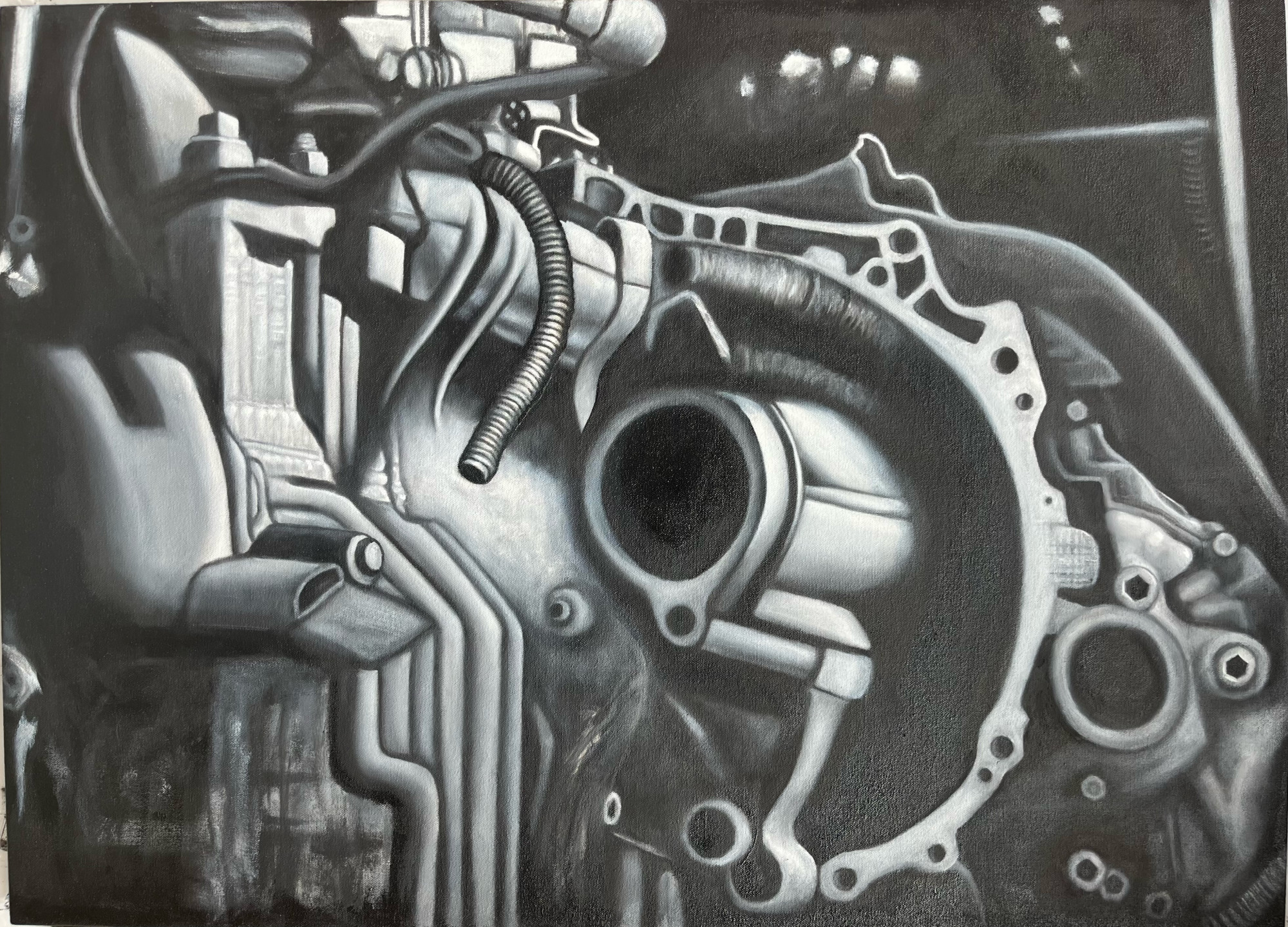

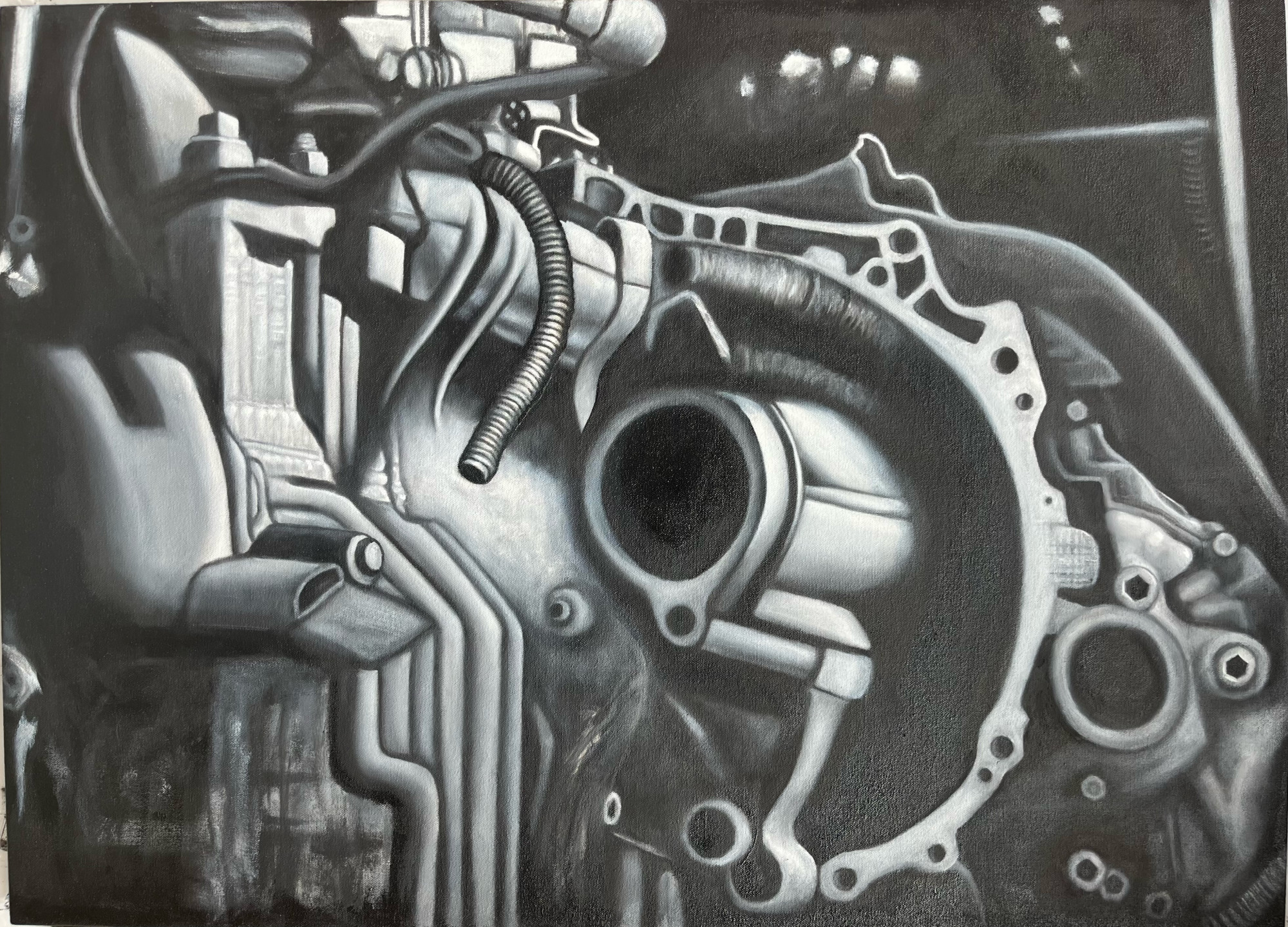

Car Engine

2024

Oil on canvas

50.8 × 77.5 cm

Marika Thunder

Clyve

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Davidson

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Gladys

2023

Oil on canvas

114.3 × 137.2 cm

Marika Thunder

Karla

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Lawrence

2023

Oil on canvas

121.9 × 91.4 cm

Marika Thunder

Roberta

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Russel

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

William

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg and Micki Meng, New York, are pleased to announce Machine Works, their first solo exhibition devoted to US artist Marika Thunder (b. 1998, New York).

Machine Works engages in a nuanced exploration of exercise machines through a photorealistic yet abstract lens to articulate the dynamic and ever-evolving interplay between humanity and machinery. The canvases eschew a comprehensive portrayal of workout apparatuses, instead presenting isolated fragments and components to deconstruct the machines and focus on their aesthetic and engineering qualities. The titles, for instance Agnes, Lawrence, and Roberta, draw from the practice of anthropomorphism—bestowing human-like identities upon objects—to humanize these mechanical entities, and somewhat obfuscate our growing dependence upon them.

There is an innate anxiety in Machine Works—one that has existed since the dawn of the Industrial Age. In 1817, E. T. A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman” presented a nightmare tale about a man who falls in love with a mechanical woman. Centuries later, this anxiety has been repeatedly borne out as justified, as developments in AI have reached the point where the nature of identity and unique thought is being challenged. Thunder’s urgent brushstrokes, combined with her meticulous attention to detail, illustrate this conflict and the latent peril of assimilating technology into the crucible of human existence.

Thunder’s measured scrutiny of these instruments imbues them with a disconcerting and almost grotesque quality, invoking parallels with the interfacing of the mechanical and the human, as espoused in the literary oeuvre of J. G. Ballard and the cinematic realm of David Cronenberg, which often highlight sexual dimensions in human-machine relations. Indeed, Thunder’s iconography can evoke BDSM, a complex spectrum of sexual consensual procedures involving power exchange, sensory exploration, and psychological stimulation.

Human motivations for working out are influenced by various factors, from personal health goals to societal pressures and psychological needs. Beyond the pursuit of physical fitness, working out can also serve as a means of psychological empowerment and preparation for the demands of contemporary life. The idea of “muscular armor” adds a thought-provoking layer to the conversation about human motivations for, and the psychological significance of, physical activity. It suggests that beyond the physical benefits, individuals might seek emotional and mental preparation through exercise to tackle the challenges of the modern world, much like knights of old preparing for the battlefield.

Embedded within this artistic dialogue lies a probing of the latent potential for metamorphosis—both corporeal and psychological—unleashed by the intertwinement of humanity and mechanical technologies. These creative expressions blur conventional demarcations, separating organic vitality from mechanical prowess. Such ruminations materialize organically, alluding to the repercussions of the symbiotic relationship between humans and machines and the sweeping implications of redefining the contours of human essence. In this way, Machine Works extends Thunder’s ongoing exploration of belonging—an inquiry into the fundamental fabric of human identity and the cognitive underpinnings that bind us universally. Yearning for belonging propels us toward the pursuit of purpose and ardor.

Moreover, Machine Works exposes the inherent aesthetic allure embedded within technological advancement. The visual exultation evoked in the upward trajectory of Karla resonates with Joseph Stella’s The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme (1939), a Futuristic creation emblematic of an era wherein mechanization automatically heralded liberation and innovation. Karla depicts gears and interlocking mechanisms with a canny, monochromatic accuracy. Still, these realistic elements are juxtaposed with white streaks of paint and an abstract outer chamber that disorients and envelops. This play with perspective adds an unpredictable edge to the machine; we’re not sure if this is a macro perspective of something handheld or a towering behemoth potentially capable of consuming us.

Thunder’s novel works delve into intricate mechanics, unveiling the myriad small cogs imperative for generating motion and the diverse forces compelled to yield to external pressures without demur.

Recent solo presentations by Thunder have taken place at Nina Johnson, Miami (2023) and Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles (2022).

Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg and Micki Meng, New York, are pleased to announce Machine Works, their first solo exhibition devoted to US artist Marika Thunder (b. 1998, New York).

Machine Works engages in a nuanced exploration of exercise machines through a photorealistic yet abstract lens to articulate the dynamic and ever-evolving interplay between humanity and machinery. The canvases eschew a comprehensive portrayal of workout apparatuses, instead presenting isolated fragments and components to deconstruct the machines and focus on their aesthetic and engineering qualities. The titles, for instance Agnes, Lawrence, and Roberta, draw from the practice of anthropomorphism—bestowing human-like identities upon objects—to humanize these mechanical entities, and somewhat obfuscate our growing dependence upon them.

There is an innate anxiety in Machine Works—one that has existed since the dawn of the Industrial Age. In 1817, E. T. A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman” presented a nightmare tale about a man who falls in love with a mechanical woman. Centuries later, this anxiety has been repeatedly borne out as justified, as developments in AI have reached the point where the nature of identity and unique thought is being challenged. Thunder’s urgent brushstrokes, combined with her meticulous attention to detail, illustrate this conflict and the latent peril of assimilating technology into the crucible of human existence.

Thunder’s measured scrutiny of these instruments imbues them with a disconcerting and almost grotesque quality, invoking parallels with the interfacing of the mechanical and the human, as espoused in the literary oeuvre of J. G. Ballard and the cinematic realm of David Cronenberg, which often highlight sexual dimensions in human-machine relations. Indeed, Thunder’s iconography can evoke BDSM, a complex spectrum of sexual consensual procedures involving power exchange, sensory exploration, and psychological stimulation.

Human motivations for working out are influenced by various factors, from personal health goals to societal pressures and psychological needs. Beyond the pursuit of physical fitness, working out can also serve as a means of psychological empowerment and preparation for the demands of contemporary life. The idea of “muscular armor” adds a thought-provoking layer to the conversation about human motivations for, and the psychological significance of, physical activity. It suggests that beyond the physical benefits, individuals might seek emotional and mental preparation through exercise to tackle the challenges of the modern world, much like knights of old preparing for the battlefield.

Embedded within this artistic dialogue lies a probing of the latent potential for metamorphosis—both corporeal and psychological—unleashed by the intertwinement of humanity and mechanical technologies. These creative expressions blur conventional demarcations, separating organic vitality from mechanical prowess. Such ruminations materialize organically, alluding to the repercussions of the symbiotic relationship between humans and machines and the sweeping implications of redefining the contours of human essence. In this way, Machine Works extends Thunder’s ongoing exploration of belonging—an inquiry into the fundamental fabric of human identity and the cognitive underpinnings that bind us universally. Yearning for belonging propels us toward the pursuit of purpose and ardor.

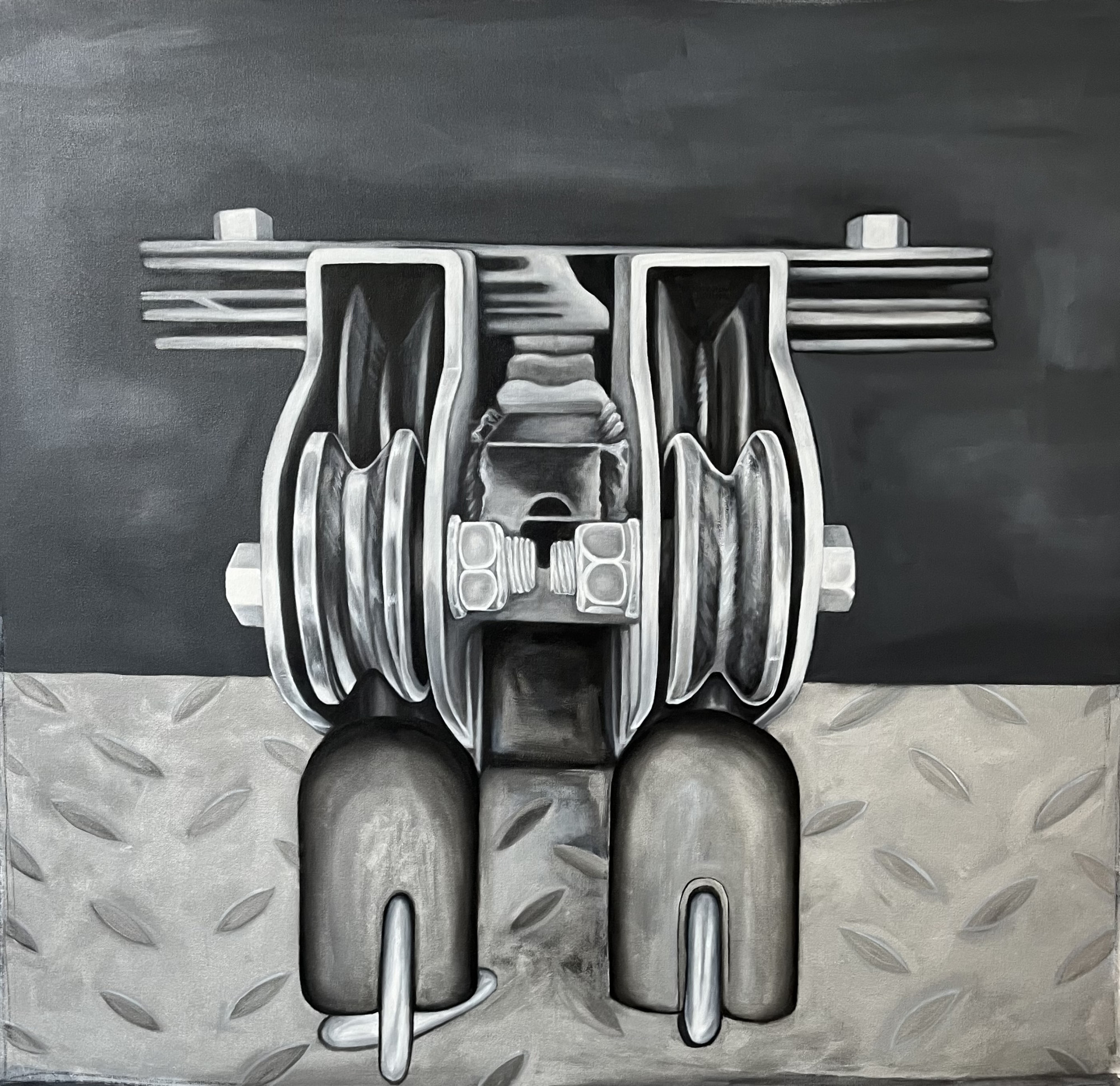

Moreover, Machine Works exposes the inherent aesthetic allure embedded within technological advancement. The visual exultation evoked in the upward trajectory of Karla resonates with Joseph Stella’s The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme (1939), a Futuristic creation emblematic of an era wherein mechanization automatically heralded liberation and innovation. Karla depicts gears and interlocking mechanisms with a canny, monochromatic accuracy. Still, these realistic elements are juxtaposed with white streaks of paint and an abstract outer chamber that disorients and envelops. This play with perspective adds an unpredictable edge to the machine; we’re not sure if this is a macro perspective of something handheld or a towering behemoth potentially capable of consuming us.

Thunder’s novel works delve into intricate mechanics, unveiling the myriad small cogs imperative for generating motion and the diverse forces compelled to yield to external pressures without demur.

Recent solo presentations by Thunder have taken place at Nina Johnson, Miami (2023) and Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles (2022).

Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg and Micki Meng, New York, are pleased to announce Machine Works, their first solo exhibition devoted to US artist Marika Thunder (b. 1998, New York).

Machine Works engages in a nuanced exploration of exercise machines through a photorealistic yet abstract lens to articulate the dynamic and ever-evolving interplay between humanity and machinery. The canvases eschew a comprehensive portrayal of workout apparatuses, instead presenting isolated fragments and components to deconstruct the machines and focus on their aesthetic and engineering qualities. The titles, for instance Agnes, Lawrence, and Roberta, draw from the practice of anthropomorphism—bestowing human-like identities upon objects—to humanize these mechanical entities, and somewhat obfuscate our growing dependence upon them.

There is an innate anxiety in Machine Works—one that has existed since the dawn of the Industrial Age. In 1817, E. T. A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman” presented a nightmare tale about a man who falls in love with a mechanical woman. Centuries later, this anxiety has been repeatedly borne out as justified, as developments in AI have reached the point where the nature of identity and unique thought is being challenged. Thunder’s urgent brushstrokes, combined with her meticulous attention to detail, illustrate this conflict and the latent peril of assimilating technology into the crucible of human existence.

Thunder’s measured scrutiny of these instruments imbues them with a disconcerting and almost grotesque quality, invoking parallels with the interfacing of the mechanical and the human, as espoused in the literary oeuvre of J. G. Ballard and the cinematic realm of David Cronenberg, which often highlight sexual dimensions in human-machine relations. Indeed, Thunder’s iconography can evoke BDSM, a complex spectrum of sexual consensual procedures involving power exchange, sensory exploration, and psychological stimulation.

Human motivations for working out are influenced by various factors, from personal health goals to societal pressures and psychological needs. Beyond the pursuit of physical fitness, working out can also serve as a means of psychological empowerment and preparation for the demands of contemporary life. The idea of “muscular armor” adds a thought-provoking layer to the conversation about human motivations for, and the psychological significance of, physical activity. It suggests that beyond the physical benefits, individuals might seek emotional and mental preparation through exercise to tackle the challenges of the modern world, much like knights of old preparing for the battlefield.

Embedded within this artistic dialogue lies a probing of the latent potential for metamorphosis—both corporeal and psychological—unleashed by the intertwinement of humanity and mechanical technologies. These creative expressions blur conventional demarcations, separating organic vitality from mechanical prowess. Such ruminations materialize organically, alluding to the repercussions of the symbiotic relationship between humans and machines and the sweeping implications of redefining the contours of human essence. In this way, Machine Works extends Thunder’s ongoing exploration of belonging—an inquiry into the fundamental fabric of human identity and the cognitive underpinnings that bind us universally. Yearning for belonging propels us toward the pursuit of purpose and ardor.

Moreover, Machine Works exposes the inherent aesthetic allure embedded within technological advancement. The visual exultation evoked in the upward trajectory of Karla resonates with Joseph Stella’s The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme (1939), a Futuristic creation emblematic of an era wherein mechanization automatically heralded liberation and innovation. Karla depicts gears and interlocking mechanisms with a canny, monochromatic accuracy. Still, these realistic elements are juxtaposed with white streaks of paint and an abstract outer chamber that disorients and envelops. This play with perspective adds an unpredictable edge to the machine; we’re not sure if this is a macro perspective of something handheld or a towering behemoth potentially capable of consuming us.

Thunder’s novel works delve into intricate mechanics, unveiling the myriad small cogs imperative for generating motion and the diverse forces compelled to yield to external pressures without demur.

Recent solo presentations by Thunder have taken place at Nina Johnson, Miami (2023) and Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles (2022).

Hoffmann + Maler + Wallenberg and Micki Meng, New York, are pleased to announce Machine Works, their first solo exhibition devoted to US artist Marika Thunder (b. 1998, New York).

Machine Works engages in a nuanced exploration of exercise machines through a photorealistic yet abstract lens to articulate the dynamic and ever-evolving interplay between humanity and machinery. The canvases eschew a comprehensive portrayal of workout apparatuses, instead presenting isolated fragments and components to deconstruct the machines and focus on their aesthetic and engineering qualities. The titles, for instance Agnes, Lawrence, and Roberta, draw from the practice of anthropomorphism—bestowing human-like identities upon objects—to humanize these mechanical entities, and somewhat obfuscate our growing dependence upon them.

There is an innate anxiety in Machine Works—one that has existed since the dawn of the Industrial Age. In 1817, E. T. A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman” presented a nightmare tale about a man who falls in love with a mechanical woman. Centuries later, this anxiety has been repeatedly borne out as justified, as developments in AI have reached the point where the nature of identity and unique thought is being challenged. Thunder’s urgent brushstrokes, combined with her meticulous attention to detail, illustrate this conflict and the latent peril of assimilating technology into the crucible of human existence.

Thunder’s measured scrutiny of these instruments imbues them with a disconcerting and almost grotesque quality, invoking parallels with the interfacing of the mechanical and the human, as espoused in the literary oeuvre of J. G. Ballard and the cinematic realm of David Cronenberg, which often highlight sexual dimensions in human-machine relations. Indeed, Thunder’s iconography can evoke BDSM, a complex spectrum of sexual consensual procedures involving power exchange, sensory exploration, and psychological stimulation.

Human motivations for working out are influenced by various factors, from personal health goals to societal pressures and psychological needs. Beyond the pursuit of physical fitness, working out can also serve as a means of psychological empowerment and preparation for the demands of contemporary life. The idea of “muscular armor” adds a thought-provoking layer to the conversation about human motivations for, and the psychological significance of, physical activity. It suggests that beyond the physical benefits, individuals might seek emotional and mental preparation through exercise to tackle the challenges of the modern world, much like knights of old preparing for the battlefield.

Embedded within this artistic dialogue lies a probing of the latent potential for metamorphosis—both corporeal and psychological—unleashed by the intertwinement of humanity and mechanical technologies. These creative expressions blur conventional demarcations, separating organic vitality from mechanical prowess. Such ruminations materialize organically, alluding to the repercussions of the symbiotic relationship between humans and machines and the sweeping implications of redefining the contours of human essence. In this way, Machine Works extends Thunder’s ongoing exploration of belonging—an inquiry into the fundamental fabric of human identity and the cognitive underpinnings that bind us universally. Yearning for belonging propels us toward the pursuit of purpose and ardor.

Moreover, Machine Works exposes the inherent aesthetic allure embedded within technological advancement. The visual exultation evoked in the upward trajectory of Karla resonates with Joseph Stella’s The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme (1939), a Futuristic creation emblematic of an era wherein mechanization automatically heralded liberation and innovation. Karla depicts gears and interlocking mechanisms with a canny, monochromatic accuracy. Still, these realistic elements are juxtaposed with white streaks of paint and an abstract outer chamber that disorients and envelops. This play with perspective adds an unpredictable edge to the machine; we’re not sure if this is a macro perspective of something handheld or a towering behemoth potentially capable of consuming us.

Thunder’s novel works delve into intricate mechanics, unveiling the myriad small cogs imperative for generating motion and the diverse forces compelled to yield to external pressures without demur.

Recent solo presentations by Thunder have taken place at Nina Johnson, Miami (2023) and Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles (2022).

Marika Thunder

Agnes

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Anuk

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Car Engine

2024

Oil on canvas

50.8 × 77.5 cm

Marika Thunder

Clyve

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Davidson

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Gladys

2023

Oil on canvas

114.3 × 137.2 cm

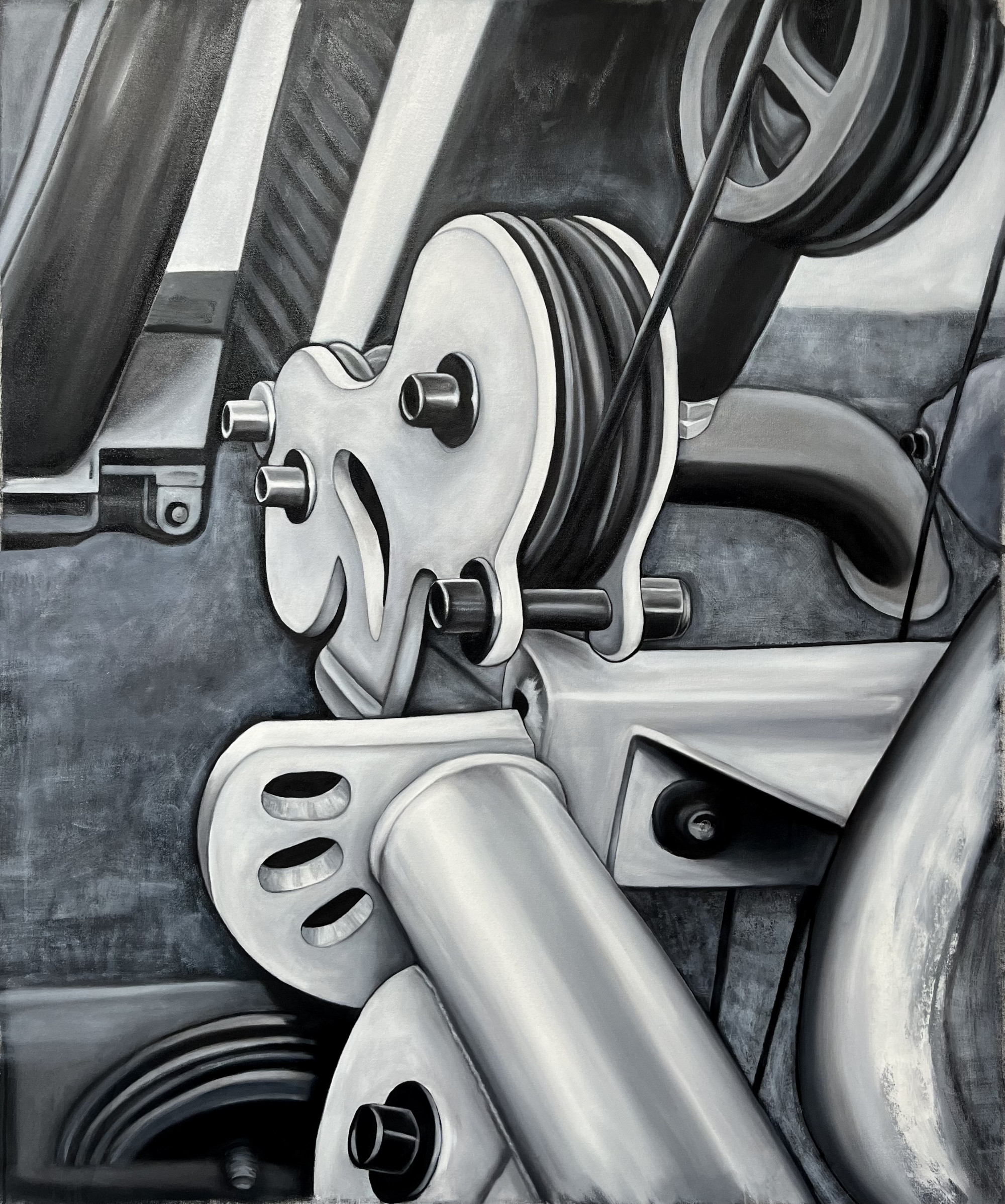

Marika Thunder

Karla

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Lawrence

2023

Oil on canvas

121.9 × 91.4 cm

Marika Thunder

Roberta

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

Russel

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm

Marika Thunder

William

2023

Oil on canvas

152.4 × 127 cm